"Writing deeply vulnerable poems about my own OCD was uncharted territory. Framing the project as memoir helped me see the road ahead."

poet Cynthia Marie Hoffman on writing a memoir in prose poems, plus tons of strategies for revising your own collection of poems

I’m excited to share another entry in the new tending section, which is a mix of essays and interviews about creative practice that do a deeper dive into a particular craft element or process question.

Today’s newsletter features Cynthia Marie Hoffman, a poet whose new book, Exploding Head, I have been eagerly anticipating for years. I read some of the earliest versions of these poems years ago when we were in a writing group together, and they’re so spooky and so skilled and moving. (You might remember Cynthia’s work from when I shared her poem Seven Darknesses over the summer.)

I’d love your suggestions of other writers and artists to feature in this series, so feel free to email me with ideas. You can just hit “reply” to this newsletter.

When I read the earliest drafts of the poems that would become Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s Exploding Head, years ago in our writing group, I was just transfixed. They were full of angels and terror and precise, unworldly imagery. They did something that I think poetry is uniquely equipped to do: they rendered a rich, vibrant world, one that is at once alien and deeply recognizable. (You can find poems from the book Birdcoat Quarterly, Image, and Electric Literature, if you want to get a sense of what I mean.) And when Cynthia started talking about the book as an OCD memoir in prose poems, I knew I’d want to hear more about the form of the book and how she’d written with the frame of memoir in mind.

You can find Cynthia on instagram at @CynthiaMarieHoffman and twitter at @CynthiaMHoffman, and if you’re going to be in Kansas City for AWP, she’s got tons of signing and events, and all that info is below.

Below, Cynthia and I talk about letting your obsessions steer your writing project, using spreadsheets and counting to revise a collection, and making a narrative arc out of your own life. And if you’re working on a collection of your own, Cynthia offers two sets of really wise and practical revision techniques.

one question for Cynthia Marie Hoffman

I know you’ve long been interested in the project book, and you’ve curated such great conversations with so many writers about that topic on The Cloudy House. I think it’s fair to say that your previous books have been projects–and I use that term in the very best way, as someone who also loves a poetry collection that opens a window into a particular world. So I was intrigued to see you talking about Exploding Head as “an OCD memoir in prose poems.”

What did it mean to you to call this book a memoir? How did thinking of it as a memoir shape your process as you drafted and revised the collection?

Cynthia

Exploding Head is about me. Which isn’t a mind-bending concept for a collection of poems, but I’m generally of the camp of poets who write from research. I’m fascinated by the boundless potential of subject matter that lies outside the self. Prior to Exploding Head, I wrote about tourism, architecture, birth, the history of medicine. My most personal collection was about my family genealogy (Call Me When You Want to Talk About the Tombstones), but even that is not as much about me as it is about the act of research.

Writing deeply vulnerable poems about my own OCD was uncharted territory. Framing the project as memoir helped me see the road ahead. And it was a way of announcing my intention to write toward something that ultimately equals more than the sum of its parts – not just a collection of poems bound together in a book, but what might binding them together make?

Memoir certainly doesn’t need to be chronological. I wrote poems about whatever aspect of my OCD occurred to me, and in whatever order. When I’d gathered about 30 or 40 poems, it was time to step back and have a look. For me, this crucial step involves identifying my obsessions (which, in a book about OCD, are pretty easy to identify!) and deciding to get really intentional about steering them.

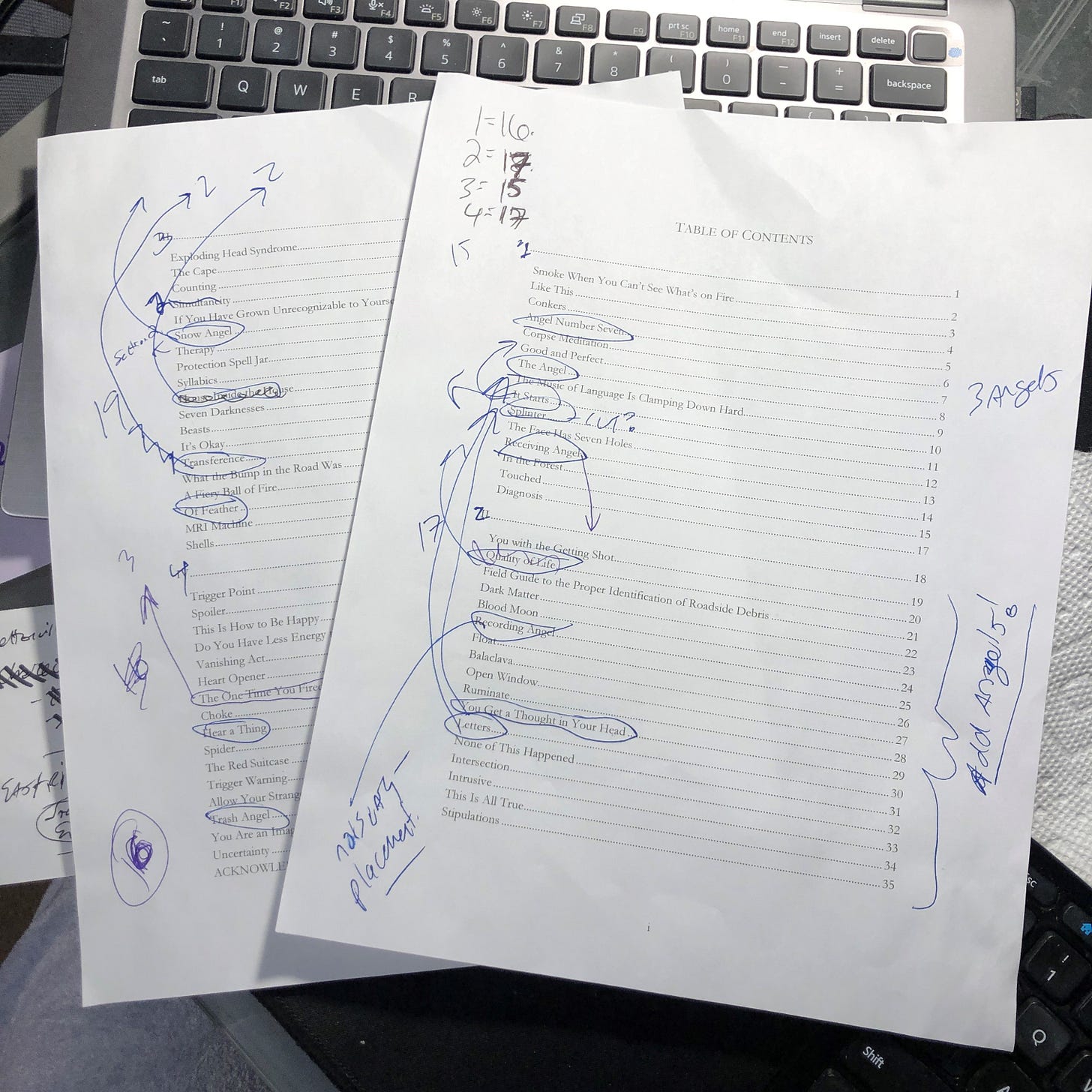

I listed the poems by subject in a spreadsheet (I love spreadsheets!). And that allowed me to immediately visualize that I had too many driving poems, not enough angels, and I’d pretty much beaten the subject of death to death. A single category with a long list of poems looks bulky in a spreadsheet, and it will feel equally heavy to the reader. I wasn’t aiming for an equal number of poems in each category, but the balance (or imbalance) of ideas should support the overall argument of the book. So at this point, I was looking at my lists and asking myself questions like, “Is worrying about car accidents so important that it justifies including twice as many poems than those about guns?” I made cuts, combined poems, and generated new work accordingly, checking my spreadsheet frequently.

Then, I had to order the poems. For a long time, I struggled with the idea that the arc of this manuscript must be the story of how my OCD got better. So I looked for that arc in the themes of my OCD and in the categories on my spreadsheet. For example, if I put all the gun-themed poems together, could I find evidence that I progressively worried less about guns? The answer was no. Did I seem to rely less on counting compulsions? Nope – they’re still here! So what was the argument of this project? For a long time, I described it like this: “I have OCD, and I just want to tell people what it’s like.” But I knew that wasn’t enough. That’s not a book.

At the very end, after 8 or 9 years of writing and thinking about this project, I had the seemingly obvious idea of setting the poems in chronological order – in the order of my lived experience. When I finally sat down and read it that way, all the way through, I noticed something. The childhood poems were terrifically lonely and fearful in a way I hadn’t fully acknowledged in my own life. I saw that I had been very lost in knowing how to deal with my symptoms. But in the poems that occur more recently, in my adult life, the language was softer. There was clear evidence that I’d gained not only insight into my symptoms, which I know was hard-won, but also self-compassion. It was immensely healing for me to realize that in fact, I have gotten better. My arc had been hiding in the poems all along; I just needed the right order of poems to reveal it. And making this sort of discovery as you write – that’s what makes a book.

But once I had ordered the poems chronologically, I had a new problem. Since the poems were written out of order, I’d had to keep establishing the subject and the timeframe of each individual poem. But once all the childhood poems were together, for example, I didn’t need to keep telling the reader that I was a child. The poems could now rely more heavily on their intertextuality.

I had to do a lot of revision to fix it. I looked at each poem and asked, “what does the reader know on this page?” When the reader turns to that page in my book, what are they bringing with them from previous pages? (Do they already know I am a parent? Do they already know there’s an angel that stands in my bedroom at night?) Anything the reader should already know from previous poems, I would need to strike. Many more poems could now start in medias res.

Once I’m thinking about balance, intertextuality, and pacing, that’s when I know I’m writing a book. That’s when (hopefully) the project starts to become more than the sum of its parts.

if you’d like to try it out . . .

I’m offering two sets of tips, depending on whether you’d like to try writing a series of poems or whether you’re arranging a manuscript (whether or not it’s a “project”).

If you’d like to try writing a series of poems:

Assuming you already have a theme in mind, the exercises below are a good way to generate ideas and to test the potential of your theme to yield a book-length collection. Pick one or try them all.

Brainstorm a list of specific ideas related to your theme. Each one could be a poem. Push to come up with as many as possible. Can you think of 20? 50? 100?

Brainstorm a list of possible poem titles.

Stretch your idea of perspective. If your central topic is a flower, for example, perhaps the wind speaks in one poem, or the soil has something to say in another. My collection Paper Doll Fetus expanded significantly through persona poems, including giving voice to objects.

Research! Read up on your topic. Watch a documentary. Take notes.

Write an exploratory journal entry to interrogate your connection to the subject. Why are you interested in the topic?

Make a list of questions you don’t know the answers to yet. Write toward the thing that troubles you.

If you’re ordering a manuscript of poems:

Try these strategies whether you’re ordering a project book or you’re collecting poems written over a period of time:

1. The Pile Strategy: Break your manuscript into manageable pieces.

Print all your poems and label them by subject. Put all the “motherhood” poems in one stack, all the “climate” poems in another stack, etc. How many poems do you have in each stack? Are the stacks balanced or imbalanced? Does the balance or imbalance make sense? If not, identify where you need to write more and where you need to cut.

Choose one pile. Put all the poems in that pile in their best order. Then do this for the next pile. Imagine you are creating micro chapbooks. (I did this with my angel poems, for example, to see how the story of the angel evolved throughout Exploding Head.)

Now, reintegrate the piles. The poems in each micro chapbook will be split apart, but there’s a good chance the ideal order of poems for each subject will be retained. (For example, my angel poems are spaced out across all four sections of Exploding Head.)

2. The Magnet Theory: Make decisions based on intertextuality.

Each poem strongly attracts some poems and repels others. Poems that rely the most heavily on information provided in other poems for impact and understanding have the strongest magnetic attraction.

Identify two or three poems that rely heavily on each other. Now, test their magnetic pull. How far apart can you place them in the manuscript and still maintain their connection?

Identify poems that seem to repel each other (on very different topics, for example). What happens if you put them close together?

3. The Breath Test: Make decisions based on pacing.

Read your entire manuscript aloud from start to finish. I can’t recommend this enough. Block time to do it. Sit somewhere private.

You will hear yourself saying things out loud that you never noticed before, even though you’ve “read” your manuscript a hundred times.

You will also get a better feel for the pacing of the book. You’ll actually feel it in your body: your breath, your energy (where do you feel exhausted, where you do feel fired up?).

Don’t just do this once. Keep checking in on your pacing when you’ve reordered poems or made significant edits.

Cynthia Marie Hoffman is the author of four collections of poetry: Exploding Head, Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones, Paper Doll Fetus, and Sightseer, all from Persea Books. Poems have appeared in Electric Literature, The Believer, Image, The Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Madison, WI. Read more at www.cynthiamariehoffman.com. You can find her on instagram at @CynthiaMarieHoffman and twitter at @CynthiaMHoffman.

If you’re going to be at AWP in Kansas City, you can find Cynthia signing copies of Exploding Head at the Persea Books table Thursday, Feb 8 at 11am. And on Friday, Feb 9 at 7pm, she’ll read at the joint Persea and Alice James Books offsite event at Casual Animal Brewing Company.

And if you’ll be at AWP, this is where you can find me. If you see me wandering the book fair, please say hi!

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. You can find my books here and read other recent writing here. If you’d like occasional dog photos, glimpses of my walks around town, and writing process snapshots, find me on instagram.

If Write More has helped you in your creative life, I’d love it if you would share it with a friend.

PS: I "re-stacked" this article. Namaste

This is exactly what I needed to read this morning. Thank you for sharing your insight into putting together a poetry manuscript. Your words are inspiring. PS: I found you when I set up @thefringe999 on substance (I started in Fracebook as #thefringe999). That alone makes this new adventure worthwhile.