Discover more from Write More, Be Less Careful

start with curiosity: approaches to research in creative writing

searching for women's lives around the margins of the scholarship, methods for organizing research, and three opportunities to write together this spring

Today’s post is in the tending section, which is a mix of essays and interviews about creative practice that do a deeper dive into a particular craft element or process question. Previously in this space we’ve talked about pitching and caring for our attention, and we’ve had interviews and guest essays from writers including Cynthia Marie Hoffman, on writing an OCD memoir in prose poems; Sean Enfield on moving from poetry to prose; and Leigh Kamping-Carder, of

, on reconnecting with your creative spark. Today I’m writing about strategies for creative research.I’d love your suggestions of other writers and artists to feature in this series, so feel free to email me with ideas. You can just hit “reply” to this newsletter.

Today’s newsletter is a little long, so if it cuts off in your email, you can read the whole thing in the browser. I’ve shared three opportunities to write together this spring—a zoom workshop on writing with creative research, a one-day workshop on pitching essays, and a one-day workshop on crafting vulnerability in creative nonfiction—and you can find all that information toward the bottom. (And I’ve got a coupon code for a 15% discount on the creative research course!)

I want to write today about methods for creative research, and because I think those two words together—creative research—are sometimes a tough sell, I want to start by telling you a story about my own most recent research project.

When I sold The Good Mother Myth last spring, I felt really confident that I knew what it was about. I’d spent years researching and writing and reshaping the outline, and I had a clear arc, seven chapters tracing the scientists (nearly all men) behind our bad ideas about how to be a good mom. After the book sold and I was writing in earnest, another question kept poking at me. I was writing about all these men, and I was reading their research and their letters and the scholarship that analyzed the impact of their work. But: these men who devoted their lives to telling women how to raise children correctly almost all had children of their own. Who was raising them?

We all know the answer to that, of course. It’s the wives. And the wives were there, too, in the research, and sometimes their children, though you have to look really closely to find them. But what were their lives like? What had they wanted, and how did they feel about their husbands traveling the world to tell other women how to mother while they were at home? What did they make of their husbands’ theories about how easy and natural and blissful it was, being a mother and being the sole creature responsible for soothing the children?

if Write More has helped you in your creative life, I’d love it if you would share it with a friend, or you can click the little ❤️️heart❤️️ at the top or bottom of this post to help other folks find us!

I want to tell you a little bit about one of my favorite wives, in part because she was so hard to find. As I was reading about Donald Winnicott, the British pediatrician and psychoanalyst who coined the term “good-enough mother,” I kept finding references to his wife Clare, a social worker with whom he frequently traveled and spoke and with whom he coauthored several articles. But she was his second wife. Where was the first? I found Alice, the first wife, at the edges of the scholarship. She was, the sources informed me, an artist, troubled, prone to hallucinations and delusions. And when, after twenty-five years of marriage, Winnicott divorced her and married Clare, with whom he’d carried on a ten-year long affair, Winnicott’s productivity soared. He finally achieved the fame he’d deserved once he freed himself of the difficult first wife who shackled him, the biographies suggested.

Finally—truly, it took me so long, reading these scholarly accounts of Winnicott’s life—I heard it, and it was like a record scratch: I know this trope. Alice is Bertha, the crazy first wife locked in the attic, and Clare is Jane Eyre, who comes along to care for Mr. Rochester and be the good wife he really deserves. But who was Alice really?

I’ll leave the longer story for the book, but for now I’ll say: Alice ended up being one of my favorite figures, and there’s so much more to her than the “crazy wife in the countryside” stereotype. She went to Cambridge, worked in the National Physical Laboratory, volunteered providing art therapy during World War II, ran a pottery studio that produced dinner ware sold in a London department store. She produced beautiful paintings, some of which are still on display. She wrote tender letters to Winnicott describing the mare and foal she watched from the home she shared with her sister toward the end of her life.

It’s hard to square all that with the image I first came across of Alice as the difficult wife who dimmed Winnicott’s genius. And as I continued my research, I found that the other wives each had their own compelling stories, and I wove those in, the traces of their dreams and ambitions and the compromises they made because of who they’d married and the times in which they lived. The wives—their lives, their ambitions—became an important additional strand of the narrative, and learning about them helped me name my own ambition as an important throughline in the book.

okay, but why should I use research in creative writing?

There are lots of good reasons to incorporate this kind of research into your creative writing. It can help widen the lens of a project that relies on personal narrative, whether that’s in poetry or prose. (Many, many of the poems in Pocket Universe, my most recent book of poetry draw on research into the history of birth, human ancestors, space, and more, and that research was essential in helping me think beyond my own experiences in early motherhood.) If you’re writing fiction, research can help deepen even imagined worlds.

There are also market reasons to weave research into memoir, of course—this is the whole thinking underneath

’s description of Memoir Plus as a category. ( makes a pretty convincing case that all memoir should really be memoir plus.) Practically, I’m sure The Good Mother Myth wouldn’t have sold as straight memoir—and that’s not the book I wanted to write, anyway.The biggest reason to do this kind of work is to follow your own deep curiosity. So if you’re interested, start there: what are you obsessed with? what are you trying to figure out?

(And this doesn’t have to be huge meaning of life stuff, at least in your initial stages—I’m getting started on an essay about the Murphy Brown/Dan Quayle debacle and what it meant to me as the daughter of a single working mother in the 90s. What’s your Murphy Brown? What are the weird things you can’t stop thinking about?)

if you’d like to try it out . . .

For a project you’re working on, start with your curiosity. What do you wonder about? Where can you widen the lens? If you’re writing personal narrative, whether in poetry or prose, what historical/cultural/demographic context sits under your story? Erica Barry shared a really great free association prompt when I interviewed her:

Make a big list or web of questions, then start searching.

Tips for organizing your research once you’ve started to gather sources:

For each source, create an entry with a citation at the top. I usually bold the citation to make it easily distinguishable from my writing about the sources. (Writing the citation is a little tedious—but doing a ton of them at the end is much more tedious, don’t ask me how I know. 🤦)

After you’ve read, write a couple sentences of high-level summary: what does the source say, and how does it answer the questions you’ve been asking? (Again, might feel tedious, but it’s a huge favor to your future self.)

Then, dive in to the nitty gritty a little: are there particular passages you might want to quote, or particular sections that are especially helpful for your work? Copy any passages into your notes, being sure to set them off with quotation marks and including a page number, if you have one. Write yourself a note about what that quotation or section means in the context of your project, or what you think you might do with it. This part always gets a little talky for me—it’s where I’m starting to think about how I’ll write with my sources, and some of those notes make it into the writing itself.

And a thought about where to keep your notes: you want something that’s digital and easily searchable, so that down the line if you’re like ugh guy who talked about Alice Winnicott and her dad, you can CTRL + F and find that source without scrolling through a million documents. I’ve used both Evernote and Scrivener for organizing research; Scrivener has a steeper learning curve but a lot more functionality. If you think you’d like to use Scrivener, keep an eye out for

’s excellent Scrivener for Creative Writers course. I took it in February, after I’d finished writing The Good Mother Myth, and learned a ton about how to organize sources and write efficiently in it that I’ll use for sure in the next book.

Finally, keep a running record to track your progress and figure out what’s next. There are certainly fancier ways to do this, but when I’m deep in a research phase, I end each day or writing session by writing notes to myself, focused on two questions: what have I learned? and what new questions do I have? (Having new questions almost always means you’re on the right track!)

and if you’d like to try creative research together . . .

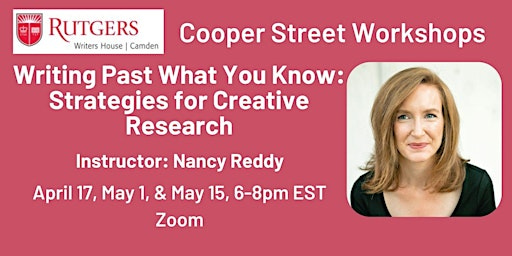

I’m teaching a three-session open-genre online workshop, Writing Past What You Know: Strategies for Creative Research, on Wednesday, April 17, May 1, and May 15 from 6-8 pm eastern. It’s $120 for all three sessions, or $30 if you’re a Camden resident or Rutgers-Camden student.

We’ll start by reading a sampling of the ways that creative research comes into poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and then each writer will develop their own project for the course. You’ll learn about and practice field methods, including interviews and observation, as well as methods for textual research into history and the sciences. Across our three sessions, you’ll write, research, and share your work, and you’ll leave the course with a new draft and confidence with methods for creative research.

And, as a special treat for newsletter subscribers, you can use this fancy coupon code—WMBLC15—for additional 15% off the cost of the course!

You can get all the info and register here.

a question for you

How have you used creative research in your writing practice? What have you read recently that drew on research?

two other ways to write together this spring

✍️ If you’re in the Philadelphia area, I’ll be leading a workshop, Learn to Pitch, on Sunday, April 7 from 2-4pm at the new Small Works Gallery at 1609 North Delaware Avenue. It’s going to super practical and hands on—we’ll do some writing, and I’ll share a couple annotated pitches and lots of resources for finding publications, editors, and pitch guides. It’s my goal that everyone will leave with at least one pitch well underway and skills they can use to write lots more on their own. The workshop is $40, with a sliding scale option and a couple comps available. (DM them on instagram if you’d like to claim a free or reduced-cost spot!)

🌲 If you’re in or around New Jersey, I’m also teaching at a one-day workshop, Crafting Vulnerability in Creative Nonfiction, at Murphy Writing’s Writing in the Pines, on April 13 from 9.15am to 4pm. It’s on campus at Stockton, near Atlantic City. There are lots of great workshops in memoir, poetry, and fiction! There’s sliding scale tuition for Writing in the Pines—$80-180 will get you a spot in a workshop, coffee/tea, lunch, and a day in really the loveliest community of writers. There are 10 scholarships available for writers aged 60+ and living in Atlantic County, and the application deadline for that is March 31st. You can read more and register here.

creative research in fiction: how Time’s Mouth author Edan Lepucki wrote 1950s Santa Cruz and 80s LA

creative research in nonfiction: how Wolfish author Erica Berry uses free association as a starting point for research

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. I’m so glad you’re here.

If Write More has helped you in your creative life, I’d love it if you would share it with a friend.

very here for this wives content

Several years ago I was reading an article about Hildegard of Bingen, and it mentioned that she might have been enclosed with an anchoress as a child. This led me to look up what the heck an anchoress is, the logistics of life enclosed in a cell, why someone (especially a woman, especially around the time Hildegard lived) would choose such a life…and now my novel about a medieval girl enclosed with an anchoress, and the present-day professor studying them, will publish in November! All because I stumbled on a random factoid in a random article (and, a factoid that may not even be true!)