a poet learns to pitch (and you can, too!)

everything I know about pitching (essays, not baseballs) + lots of links and resources

Today I’m excited to share another entry in the new tending section, which is a mix of essays and interviews about creative practice that do a deeper dive into a particular craft element or process question.

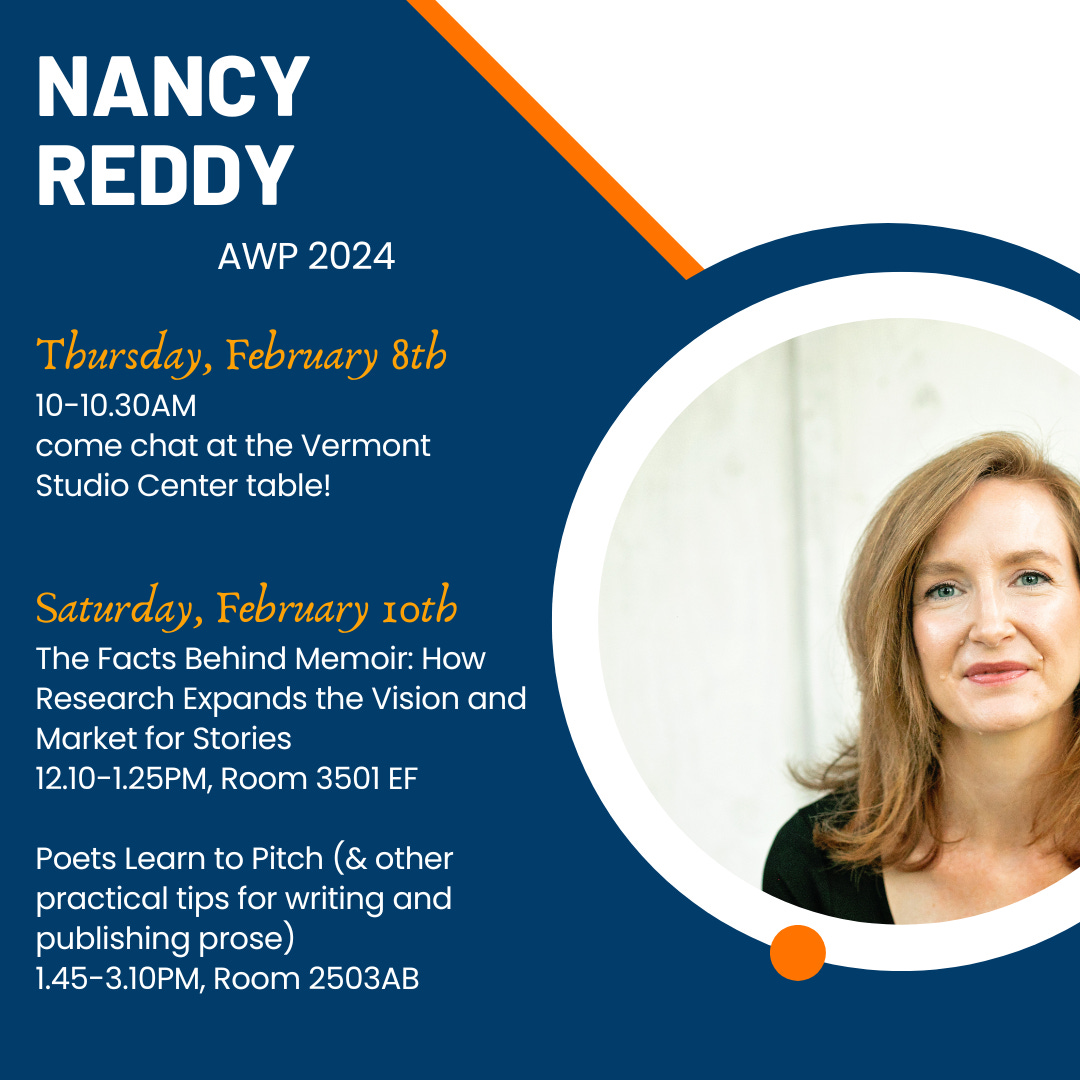

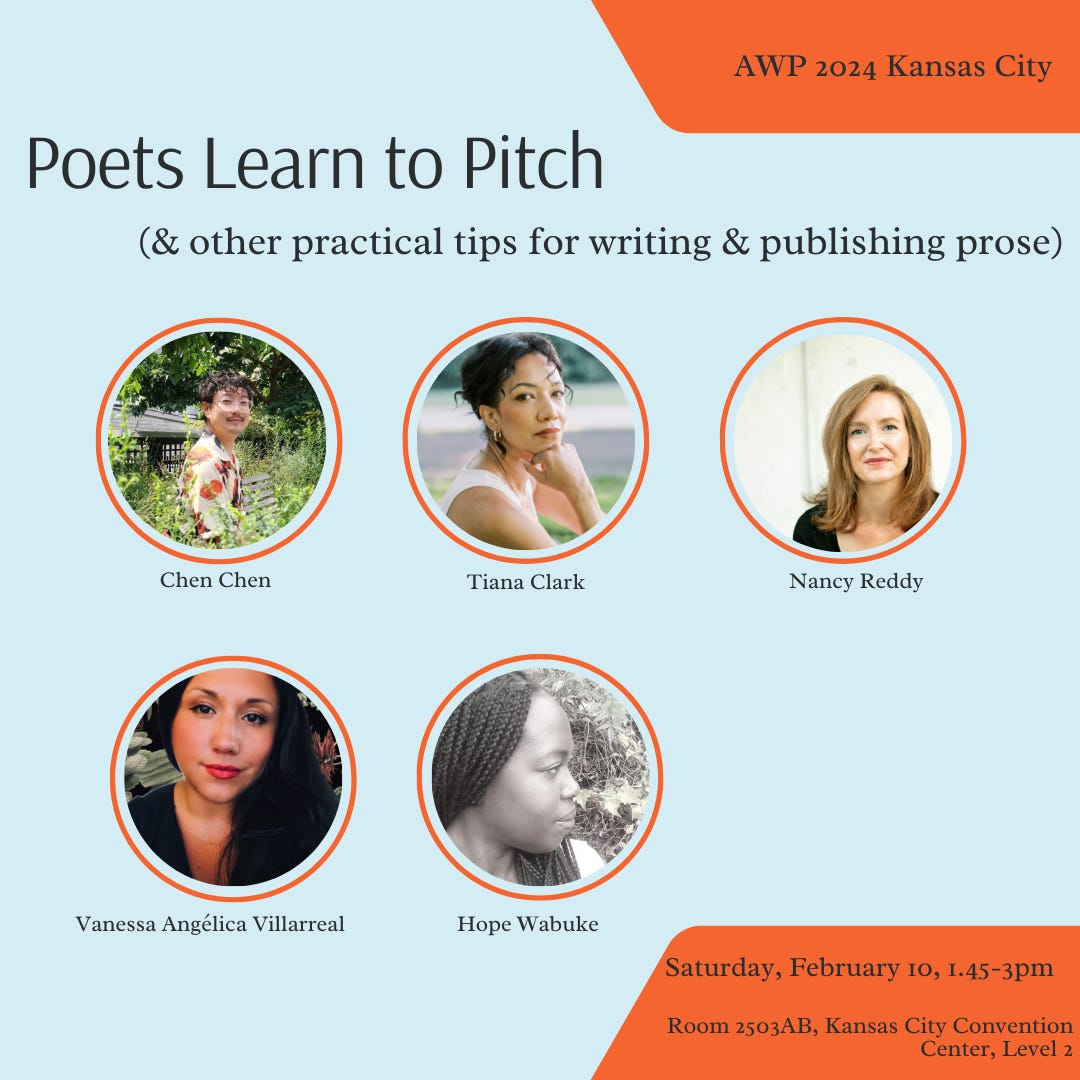

In advance of a panel I’m moderating at AWP this weekend about poets writing prose, I wanted to round up everything I’ve learned about pitching. Below, you’ll find a mix of philosophy and tips, plus tons of resources and a genuine Pitch That Worked. This one’s a little long, in part because I’ve shared a full (successful!) pitch in it, so if it cuts off in your email, you can click on the headline and read it in your browser.

I’d love your suggestions of other writers and artists to feature in this series, so feel free to email me with ideas. You can just hit “reply” to this newsletter.

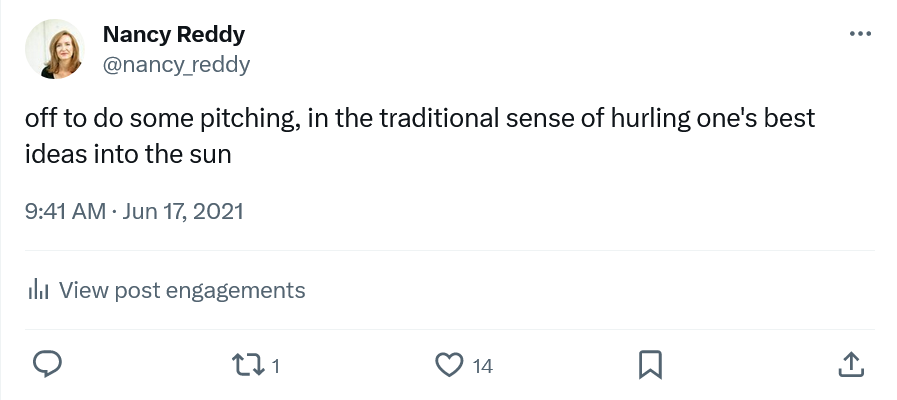

I was never particularly Funny on Twitter™, and now I’m not really there at all, but I stand by this one:

Sometimes pitching really does feel like just taking all your best ideas and chucking them into space. But the thing is: that’s the only way you’ll actually know what lands.

So many things about writing and publishing can feel really obtuse and unnecessarily complex, and I’ve found this to be really true as I’ve moved from poetry (a genre in which I have a significant amount of training) to prose (where I still sometimes feel like I snuck in and am about to be found out at any moment). In my MFA, we got some explicit instruction around submitting to literary magazines—write a brief, normal cover letter; keep a spreadsheet to track where you’ve sent things and what happens—and a kind of overarching philophy—the idea that submissions are the business side of writing, like doing your laundry. You have to do it, but you don’t want to let it encroach on your writing time.

But once I started writing prose, I discovered there was a whole other process I didn’t know anything about. It turned out that, in lots of places, you didn’t submit your work. You sent a pitch. The only problem was that I didn’t know what that was or how to write one.

There’s tons of good advice on how to write a pitch on the internet, and I’ll round some of that up below, but what I really want to offer is a kind of philosophy of pitching—how pitching can help refine your ideas and develop your sense of the audience for your writing.

if Write More has been helpful in your writing life, click the little heart at the top or the bottom to help other writers find us!

pitching is an engine for new ideas

One key difference between pitching and submitting is that a pitch is an idea. It’s not yet a finished product, or even a draft. It’s an outline, or a promise.

And to write a good pitch, you’ll need to learn to think not just about the quality of the writing but about the readers you’re hoping to reach and what you’re offering them. If you’re pitching something, you’re thinking about the fit between your piece and your target publication. So that means you need to be able to not just say what you’re going to write but also why now, why this publication and this audience, and why you should be the one to write it.

Those are the key components for a good pitch (more on that below), and they also provide a framework that can shape your reading and generate new ideas. If you have a topic in mind, thinking about the publication, audience, and specific kind of piece you want to write can help you brainstorm possibilities. The same topic—say, pelvic floor physical therapy—could be spun out in a ton of different directions: a personal essay for a women’s magazine, an op-ed about difficulties accessing women’s healthcare and the pernicious expectation that our bodies will just be a little broken after pregnancy and birth, a piece of service journalism about why you might want pelvic floor pt and how to access it. (Can you tell I’ve pitched that idea around a ton? It hasn’t landed . . . yet.)

And this process can also go in the other direction: if there’s a place you’d love to be published or an editor you want to work with, see what they’re publishing and how your work might fit into that. Twitter used to be especially great for that—editors would just tweet out the kinds of pieces they were looking for. Has anything replaced that? Is that happening on Threads? Let me know if you’ve got good ideas for finding editors and pitch guidelines.

Looking for series or recurring features can be especially helpful. (I really love the New York Times’s Letter of Recommendation and Vox’s Even Better series, though I haven’t cracked the code in either spot yet.) Once you’ve got your eye on a particular series or feature, read a ton of them, then think about how your work might fit in.

my best tips for writing a good pitch + a real, live example

When I started trying to learn about pitching, I kept coming across one name: Tim Herrera. At the time, Herrera was the editor for the NYT’s Smarter Living, and now, he’s gathered all his good advice on pitching and freelance life more broadly on his newsletter,

, where you can read about how to pitch stories instead of ideas and find a great round-up of 70+ pitching guides. Those are still the best, most comprehensive guides I’ve found, so if you’re new to pitching or just want more guidance, I’d start there.Instead of recreating that advice here, I thought I’d share an example—the pitch I sent to Catapult’s Don’t Write Alone series (RIP), about how to make the most of a writing residency. I’ve included a couple of italicized notes in brackets.

freelance pitch for Don't Write Alone: setting yourself up for success at your writing residency [subject line names the series and includes a proposed headline]

Dear Stella,

I'm writing to pitch a piece for Don't Write Alone, How to Set Yourself Up for Success at Your Writing Residency. I'm imagining my piece as a counterpart to Maria Robinson's great "Get Thee to a Writing Residency," which provided such great helpful tips on how to apply for residencies. It's meant for writers who are dreaming of getting away to write and addresses the anxiety many of us feel when we finally get a big chunk of time to work: now that I've got all this time, how can I make the most of it? [opening says what my proposed piece is + how it fits in with the rest of the series]

My piece provides tips from my own experience and from interviews with other writers about how to set yourself up for success once you're ready to head out for your residency--and it will be equally useful for writers who've been selected for prestigious places like Yaddo or MacDowell and folks who've made their own residency with a night or two at an AirBnB or by housesitting for a friend. (I think it's really important that we talk not just about fancy, selective places, but also the kind of ad hoc and self-made residencies writers create themselves--I interviewed several writers for a piece about at-home and self-made residencies during an earlier phase of the pandemic.) [specifies the substance of the article—my experience + other writers; if you’re going to report some aspects of your story, this is where you can name who you’d interview and what research you’ve already done]

Key topics for the piece include:

how knowing what you need for your writing practice can help you select a residency that's a good fit (in my own writing life, I need to move and food I don't have to make decisions about--so that means someplace like the Vermont Studio Center, which has trails and three delicious meals a day is great--and an AirBnB at the shore off-season, where I can walk on the boardwalk and heat up some pre-made meals I've brought with me is great, too! other writers I know need to be close enough to drive, so they can bring all the books they want, or they need the security of not going too far from home, so they can return if parenting and/or eldercare responsibilities arise)

creature comforts--what to pack (my go-tos are fuzzy socks, chocolate, and good tea)

how to set goals and intentions for your time--at a residency, there's an important balance between having high hopes for what you'll do but also not putting too much pressure on yourself.

and, partnered with the above topic of intentions--setting parameters around technology and connection to the world outside the residency. Some writers love to be really away when they're at a residency, while others thrive on being able to stay in touch with family or friends. (Hannah Bae's piece, A Person of Color’s Guide to Navigating Writing Residencies, explained how being near friends or family made her residencies much more comfortable, which I think is such an important perspective, especially considering how white and isolated the spaces of residencies often are. I always think of the Carmen Maria Machado short story "The Resident," where the writing residency becomes a kind of horror story!) In either case, I think it's helpful to establish parameters while at a residency--it's one thing to carve out time to chat with your partner and another to while away a weeklong residency on twitter!

[this list is long! but it gave me the structure for the piece and showed the editor exactly what I was going to write. (In my email, each item was bulleted, but substack didn’t like that formatting with the block quote.) I went with bullets and bolding here to make it easier for the editor to see the sections and big ideas]

One big takeaway from the piece is that there are lots of ways to think about being "successful" at a residency--a residency can sometimes be a great way to produce big word count--but it can also be a time for a kind of deep thinking that's hard to do in the midst of the distractions of daily life. I like to think of residencies as an opportunity to open a door in your brain that allows you to see your whole project differently. The piece will guide writers toward setting intentions that will help them make the most of whatever residency time they have.

In the piece, I'll draw on my own experience at residencies and also include interviews with other writers. Though I can't speak (as Hannah Bae does, for example) directly to the experience of being a person of color at a residency, I'll be sure to include a range of sources and consider issues like accessibility for writers with disabilities and the ways that residencies aim to make themselves workable for parents and others who can't just jet off into the woods for a month at a time. I think this piece will be a great addition to the lineup of practical, encouraging resources Catapult offers through Don't Write Alone! [two more paragraphs about what readers will get from the piece and how it fits in with what Catapult’s already published on this subject; you might not need this much detail in every pitch!]

A bit about me: I'm a poet, essayist, and professor. My recent books include the poetry collection Pocket Universe (LSU, 2022) and the anthology The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood (UGA, 2022). My most recent essay (at Catapult!) is about Kate McCallister, the mom from Home Alone, as "a messy and magnificent model of motherhood." I've written craft pieces for Poets & Writers, The Millions, and elsewhere, and my essays have also appeared in Slate, Romper, Electric Literature, and elsewhere. My website is here, and other recent clips are here. [quick bio; I usually tailor this a little to highlight whatever I’ve written that’s most relevant to the thing I’m pitching]

Thanks for considering my pitch! I'll look forward to hearing back from you.

Nancy Reddy

That pitch is way longer than most I’ve written, and you often don’t need quite that level of detail—but I wanted to share it here because it shows something else that can be really helpful about pitching: by the time you’ve outlined the structure of the piece in a pitch, you’ve proven to the editor that you can get right to work, and you’ve made a roadmap for yourself. I’ve seen pitching advice that says to go super short, and while I’m sure there are editors who don’t want to see more than a paragraph or so, there are definitely other editors who would see a single paragraph and not be convinced you actually know enough about what you want to write. You should always check pitch guidelines for the publication, and, even better, for a particular editor, if you can find them.

If you want to see how the piece turned out, you can read it here.

a friendly note about pitching and rejection

When I first started pitching, it felt really risky. If you’re submitting to literary magazines, you bundle up your best batch of poems and upload them into a little portal. You wish your work the best, and leave it alone to try to fight its way to the top of the slush pile. But when you’re pitching, you’re usually typing up your best ideas, then shooting them directly into an editor’s inbox. It can feel a lot more personal, and the rejection can sting more, too.

I’ll write more about rejection in an upcoming piece, but for now I’ll say: one thing I’ve learned as a writer is that no amount of rejection is actually fatal. It might pinch a little, and some rejections do hurt more than others, but honestly, that’s part of the whole deal.

The most common rejection, I’ve found, is silence, which is a bummer, but oh well. The second most common rejection is the mysterious “this isn’t a fit” or once, memorably, the note that a piece (that I’d drafted on spec, after the editor was interested in my pitch, sob!) “isn’t quite right for our mix.” What do those rejections mean? Who knows! They’re not information. (Some rejections *are* information, though I think that’s relatively rare; we’ll talk about that soon, too.)

But you know the rejection I’ve never once gotten? Never once has an editor emailed back to ask me who I think I am and why I thought these ideas were good enough for their esteemed publication. Even when I’ve perhaps aimed a bit too high or sent out an idea before it was truly ready, never once has an editor scolded me for trying. (Maybe they thought it, who knows? Most likely, they just sent a generic rejection and moved on with their life, which is fine!)

The only thing I’ve found that feels even worse than rejection is not trying.

If you’re going to be at AWP this week, I’d love to see you!

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. I’m so glad you’re here.

If Write More has helped you in your creative life, I’d love it if you would share it with a friend.

I'm a poet publishing a novel in the fall, so I'm starting to think about pitching pre-pub essays...this could not have come at a better time for me, thank you!

The only thing worse than getting rejected is seeing the place you pitched to use the EXACT story idea you suggest a month later, written by one of their other writers. Yep, still bitter about that one!