Discover more from Write More, Be Less Careful

"I’ve had to fight for this time but also accept that what’s possible shifts from season to season."

poet and professor Bronwen Tate on the "beautiful exhaustion" of life with small children and how her daughter's artwork reminds her that "ideas come in the making"

Hello there! Welcome to Write More, Be Less Careful, a newsletter about making space for creative practice in a busy life. My next book, The Good Mother Myth, will be out in January 2025, and you can pre-order it now!

This is a good creatures interview, a series that explores the intersection of caregiving and creative practice. I’m so excited to showcase people doing lots of kinds of caregiving—people caring for kids or pets or other family members and/or caring for space through gardening or community work or activism—and lots of kinds of creative work.

If you know (or are!) a good creature whose work we should feature, send me an email—you can just reply to this newsletter.

Today’s interview is with

, a poet and professor and all-around fascinating thinker who I actually got to know through this newsletter! After she told me via email about how she’s used Helen Sword’s Air & Light & Time & Space in her own writing practice and with the grad students she teaches, I asked her to share that genius perspective with everyone for the newsletter, and you can find that interview here.Below, Bronwen and I talk about her many, many kinds of creative work, the inspiration she draws from her daughter’s art practice, and how her sense of time has shifted as her kids have grown.

Who do you care for?

I care for (and am cared for by) my daughter Vesper (8), my son Gen (11), and two small cats, Clemmie and Mousekin. I share this caretaking with my husband Caleb, who recently took the children to Oregon for their spring break (which does not align with mine! why?!). There, he cared for the children with help from my parents and sister and his friend Wendell, which allowed me to care for my friend Austen, who was recovering from a bike accident and stayed in my son’s Lego-filled room for a few days. I also rely deeply on relationships of mutual care with friends like Anna, who calls me from Minnesota every Monday to set writing goals for the week, Bridget, who’s on hand whenever I have a thorny teaching question, and Hannah, who walks around South Pond in Cambridge, MA while I walk the paths of Pacific Spirit Park in Vancouver as we talk about whatever crisis or romantasy novel or new way to cook chickpeas is on our minds.

What kind of creative work do you do?

I’m a writer and creative writing professor at UBC in Vancouver, Canada. Poetry is my central creative practice. I’m also working on a creative writing teaching resource book in collaboration with my colleague John Vigna, and a collection of linked essays about the last three years of the experimental college where I taught before joining UBC in 2020 (Yep, that 2020. Ask me about driving across country with two kids, crossing an international border, quarantining for two weeks in a hotel room, then starting a new job!). On any given day, my creative work might also take the shape of knitting an acorn hat for my son’s teacher who’s expecting a baby, practicing the hammer-on for the lick in Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” on guitar, or trying to figure out how to fold ravioli with minimal air bubbles.

What’s changed in your creative life since becoming a caregiver?

When I think of a time before care-giving, I picture the first California apartment I lived in at the start of my PhD program. Caleb would leave most evenings to wait tables, and I’d hang out and read essays for class or knit complicated silk lace shawls while listening to audiobooks. I recall a sense of spaciousness from that time: it’s summer, and you have a big iced coffee in a jam jar, and you don’t know what time it is because no one needs anything from you.

Before my son was born, I had a few years of miscarriages and lingering blood clots and “good ultrasounds” followed by losses. By the time I had a child, I was certain how much I wanted one. Every difficult thing was washed in a watercolour of gratefulness, a feeling of “this could have gone differently.” Those early years, I was writing my dissertation (and poems too, sometimes, on the side) and then teaching in a postdoc, and my husband and I shared the care of one and then two children between us, with a bit of part-time daycare for the older kid. I would get up at 5:30 or 6 am to drive from San Francisco to Palo Alto to teach and then race to get on the highway before rush hour traffic and get home in time for Caleb to leave for his dinner shift.

As for so many people, the change was time.

Those years in San Francisco with a baby, then a toddler, then a toddler and a new baby, finishing the PhD, applying for hundreds of jobs year after year, I remember long Saturdays when Caleb worked brunch shift and I’d take the children to the SF Botanical Garden so the baby could nap in the stroller or crawl around and try to eat leaves and the toddler could run and not get hit by a car before I could dash after him. Beautiful exhaustion. Anything creative came at the frayed edges of the work of necessity.

Recently, I feel myself coming to a new shore. My children will read or build Lego or draw for hours. Or they’ll run off and play with the kids down the hall in our apartment building and only come back as a feral crew of five in search of snacks two hours later. I’m starting to feel my sense of time shift again. I spoke recently with an MFA student with a baby and remembered when sitting in a dentist chair felt like a restful reprieve because no one needed me, no one would cry or break something or get hungry. I don’t feel that way anymore.

What are some ways care-giving fosters creativity and vice versa?

My children bring me back to the sensory, which is essential for creativity. Care-giving aligns with textures, cooking, curiosity, play, getting lost in a book, jumping in a lake. My children want these things, and I want these things! Meanwhile, there’s email. I’m nearing the end of another academic term, and I feel summer ahead as a time for children and art making, sometimes together, sometimes apart.

My daughter (8) is an artist. If someone says “Oh, that’s a great picture, do you want to be an artist when you grow up?” she says, “I’m an artist now.”

She makes art without all of the adult baggage of self-doubt and throat-clearing. She jumps right in with joy and just explores her material. Sometimes she’ll ask me, “What should I draw?” and then even as I start to reply, “It’ll come to you in a minute,” I see her pencil begin to move: it’s there! As I’ve been drafting these responses, I’ve followed her journey with a project. She found a bunch of cardboard scraps from a chain reaction her brother was working on. First, she arranged them in a pattern on the couch,

then when the couch was needed, she nonchalantly gathered them up and remade her work on the table on paper.

Later, I came back and found the piece on the living room floor with detailed illustrations and and notes (including “treshr” and a “taylor swift sekshin!”).

When I’ve been busy with admin tasks (annual review, taxes, final grades, committee report), I can start to feel disconnected from art making, to wonder if I have anything to offer. Seeing Vesper make art reminds me that, as I tell my students over and over, ideas come in the making, discoveries emerge from our material engagement. I know this. But seeing her complete painting after painting makes it undeniable.

On the flip side, creativity fosters care-giving through respect for mess and dreamspace, which are essential to art and also to childhood. I think of this passage from Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes about the books her mother gave her:

One of those books was Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters in which Bambara, in the dedication, thanks her mother, “who in 1948, having come upon me daydreaming in the middle of the kitchen floor, mopped around me.” In that dedication, I saw something that my mother would do; I saw something that she had done. My mother gave me space to dream. For whole days at a time, she left me with and to words curled up in a living room windowsill, uninterrupted in my reading and imagining other worlds (Ordinary Notes, 85).

What do you do to help activate the switch (if it is a switch) between creative-brain and care-giving brain? (Is it possible to switch?)

For me, it’s always been a question of three brainspaces. I’ve been the main or sole source of income and health insurance for as long as I’ve been a parent, so I’ve been teaching and writing continuously. From the start, I’ve felt good about leaving to work, coming back to children, how each can feel like an escape, a break from the other. There’s housekeeping, of course, in both my home life and my work life. I often have a messy house, but I cook beautiful food and I’m pretty good with spreadsheets. And there’s teaching, which often feels like a mix of creativity, care-giving, and housekeeping.

What I’ve had to fight for, though, is the art making itself. Teaching (and all the admin that comes with the full-time university jobs I’ve been lucky to secure) and parenting both have clear accountability, a hunger, a clamour: When will dinner be ready? Have you graded the assignment yet?

Where in those competing to-do lists do I make something uncertain like a poem?

I’ve had to fight for this time but also accept that what’s possible shifts from season to season. In my newsletter, I’ve written about making a container for inefficiency and about how useful I’ve found Oliver Burkeman’s insistence on the necessity of declining to clear the decks.

Recently, I’ve been cultivating the image of a walled garden. The walls need to be fierce to keep things out, but inside things can be slow and meandering. There’s space for unpredictable growth, happy accidents, periods when the only progress is hidden underground. I picture myself stepping through a door in the wall.

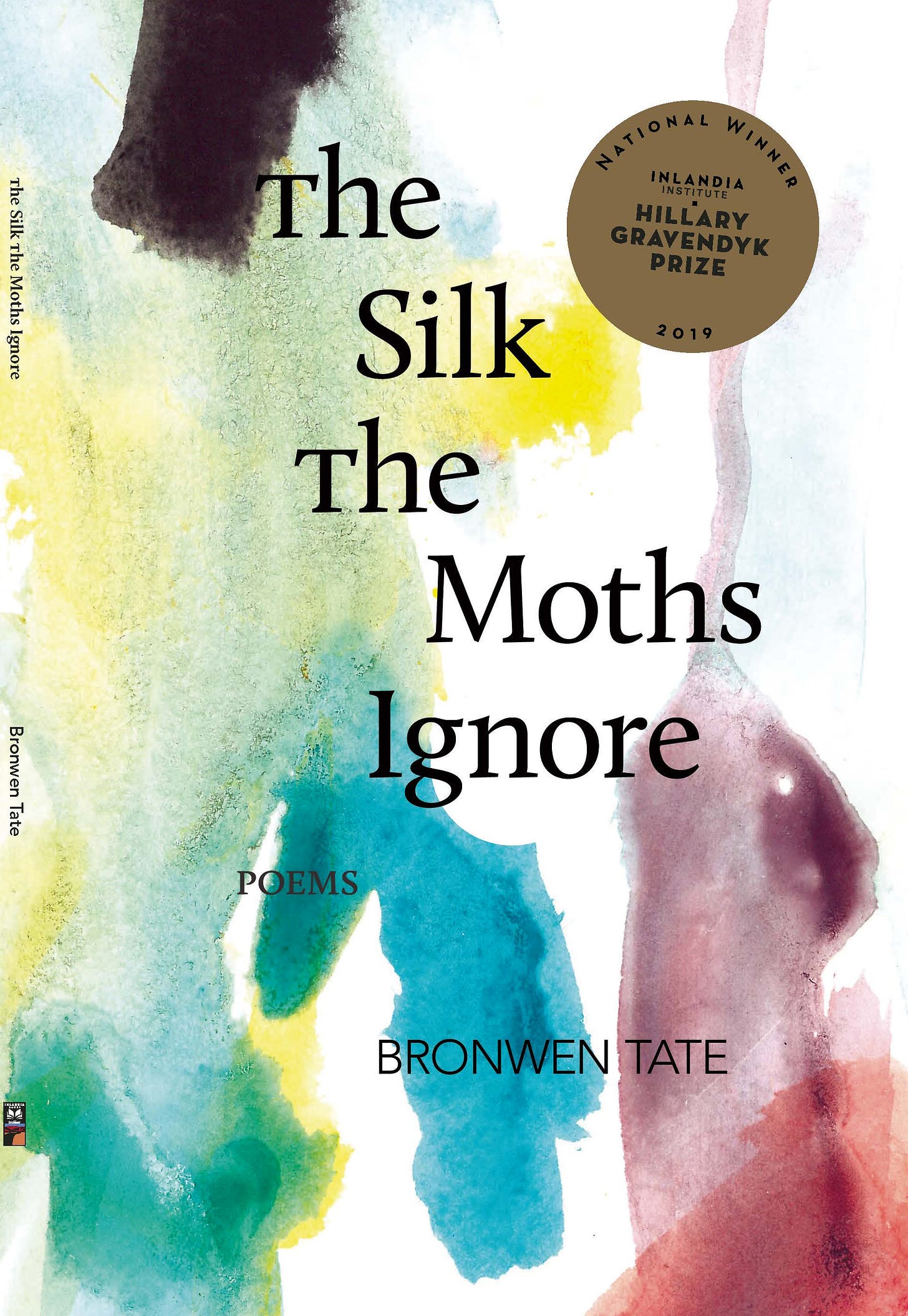

Bronwen Tate is the author of the poetry collection The Silk the Moths Ignore. She is Undergraduate Chair in the School of Creative Writing at UBC in Vancouver, where she offers courses in poetry, creative nonfiction, literary translation, and the teaching of creative writing. In collaboration with UBC colleague John Vigna, Bronwen is co-writing a creative writing pedagogy book under contract with Bloomsbury Academic. You can find Bronwen on Instagram at @bronwentate.

You can read Bronwen’s strange fairy tale poem in TYPO or a selection from a long poem about creative work and caregiving at Court Green, or listen to Ada Limón read and talk about her poem “Bruised Peaches” on The Slowdown. You can also hear Bronwen in conversation with Han Vanderhart on the Of Poetry Podcast, or even listen to her read some high school sonnets on Writers Read their Early Sh*t with Jason Emde.

She also writes the great newsletter Ok, But How? which you’ll definitely want to subscribe to, if you’re not already!

more playful ways into writing

on using anagrams to get started (another guest post by Brownen!)

on making it weird in revision

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. You can find my books here and read other recent writing here.

If Write More has helped you in your creative life, I’d love it if you would share it with a friend.

This is so lovely. The sensory, as the Aurist's interview with Paul Lynch just discussed, is so essential to writing. Kids have it naturally - and yet somehow, somewhere, it can get hard to access as an adult. It's on my brain today...

Yes to the inspiration of kids’ art! I so miss the days when my home was graced with it. Vesper’s art brings it all back. It’s incredible. The taylor swift sekshin! 😍