"with kids, I’ve learned to think of my writing year in terms of seasonality"

poet Mia Ayumi Malhotra on her new book MOTHERSALT and learning to adapt a creative practice alongside mothering

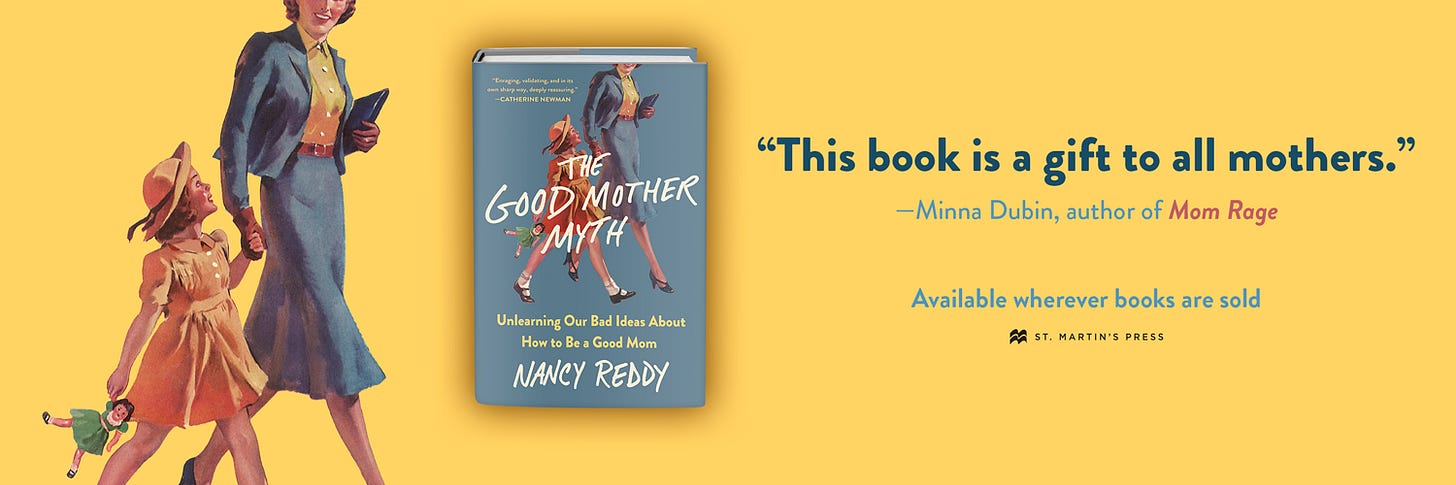

Hello there! Welcome to Write More, Be Less Careful, a newsletter about making space for creative practice in a busy life. If you’ve found inspiration in the good creatures series, I think you’ll love my new book, The Good Mother Myth, about motherhood, ambition, and making art.

This is a good creatures interview, a series that explores the intersection of caregiving and creative practice. If you know (or are!) a good creature whose work we should feature, send me an email—you can just reply to this newsletter.

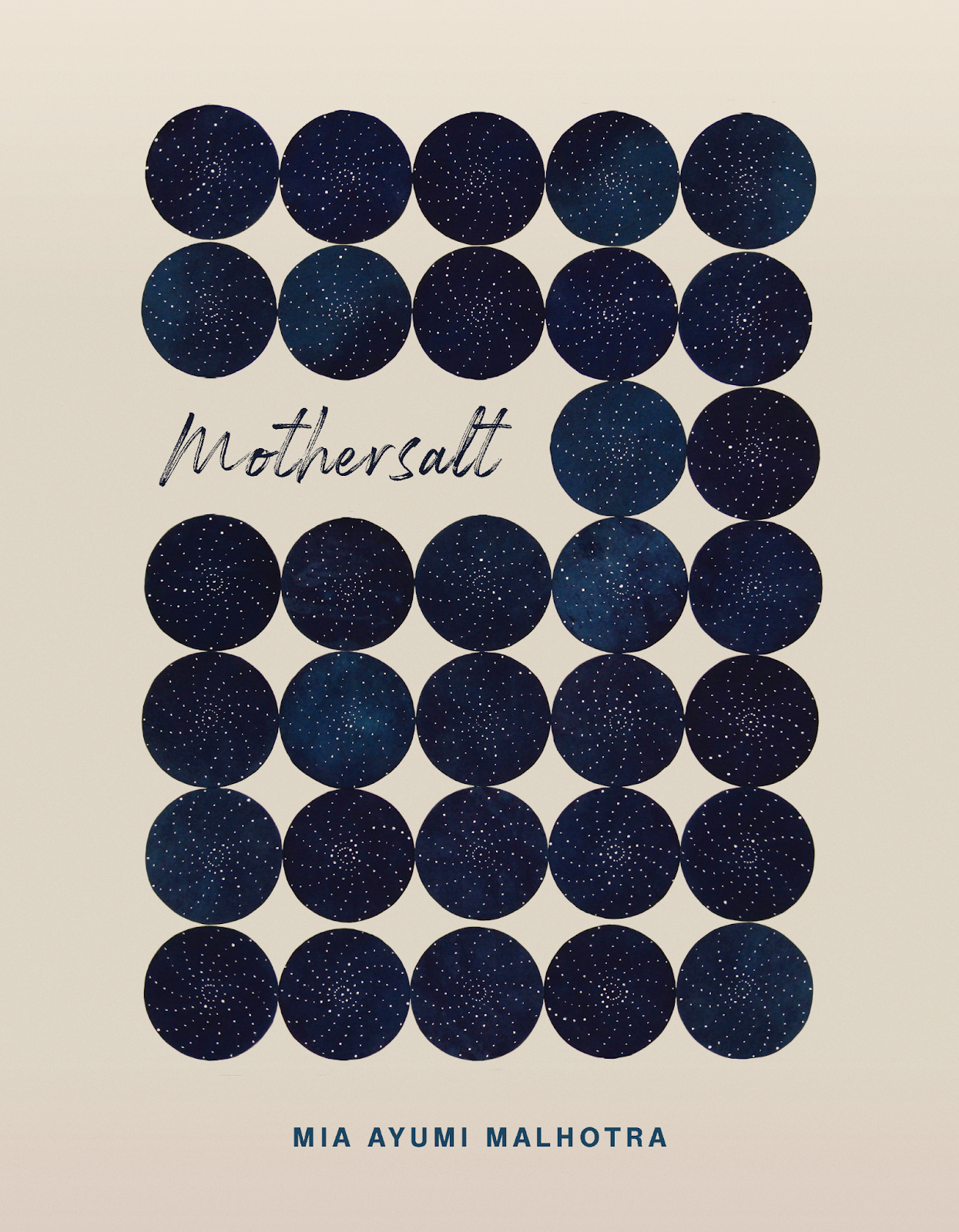

Today’s interview is with Mia Ayumi Malhotra, whose new book Mothersalt is out now. The poems in Mothersalt are gorgeous meditations on pregnancy, birth, and motherhood, the kind that ask you to slow down and really dwell inside the lines. Below, we talk about having a really wide creative practice, taking inspiration from Ruth Asawa, and how the right soundscape can set the stage for switching from caregiving to deep creative work.

Whom do you care for?

These days, I care primarily for my two children—beyond that, my web of care extends in many directions: family friends, relatives, poetry students, my beloved circle of artist-mothers, members of our spiritual community, the choir that my kids and I sing in. When it comes to the many forms of care I’m privileged to give and receive, I’m blessed beyond measure.

What kind of creative work do you do?

I have a lot of creative habits—embroidery, observational drawing, singing—but my primary work is making poems (and poem-like things). I started writing poetry as an undergrad, in a Flor y Canto workshop led by writer and activist Cherríe Moraga, co-editor of the landmark anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Thanks to Cherríe, my first real encounters with poetry were in the midst of a field rich with intersectional identity, political and historical engagement, and of course, song. Since then, I’ve written and published several collections of poetry and am currently at work on a project about music and the interior life. Recent experiments range from a heroic crown of sonnets inspired by the pipe organ to a series of “breath sculptures”—collaged bits of language that drift across the page, mostly in response to my studies in voice. Earlier this year, I learned that the word “poet” comes from a root word that means, “one who gathers / heaps,” or “one who piles up,” which I’d say is a fairly accurate description of the way I write.

What’s an adjustment you’ve had to make to your creative process?

With kids, I’ve learned to think of my writing year in terms of seasonality; summer has a completely different rhythm than winter, for instance, and while the summer months do enable certain forms of work, there are others—deep revision, for instance—that are incompatible with the sort of attention and time I have at that time of year. For the most part, I find myself anticipating and working with these shifts, rather than against them, and I appreciate the unique way that they structure my work.

I’d say the biggest shift in my creative process happened back in the spring of 2020, during those months when no one was leaving their houses, and parks and playgrounds were all fenced off with caution tape. It feels like a bad dream, thinking back to that time, but thanks to poet and artist Éireann Lorsung, I did develop a vibrant observational sketchbook practice that year. Lucky for me, because it was impossible to sustain my normal writing habits while homeschooling and caring for my kids (believe me, I tried!). I think it’s safe to say that the practice of documenting daily life, walks, and plant life are what saved me during those years. Even now, my kids talk about going out into the neighborhood and gathering oxalis flowers in the spring, pounding acorns to make dye, sketching apple cores to document their transformation / decay over time… What I learned from those years is that certain artistic practices can coexist with mothering in surprising and even essential ways, especially when they engage the hands, the feet, the body in motion. Practices that don’t rely on screens or electronic media, that are embodied—these are soothing to the mind and spirit, not to mention accessible to children in a way that typing on a laptop is not.

another good creature, Jennifer Case, on embracing multiple kinds of creative practice

Is there someone who inspires you that both fosters a creative practice and is a care-giver?

I learned about the artist Ruth Asawa a number of years ago, but it wasn’t until this spring, when I visited the SFMOMA’s retrospective of her work, that I fully understood the breadth of her creative practice and its deep integration with her family life. In addition to the looped-wire sculptures for which she is most well known, Asawa’s body of work includes drawings, bronze castings, clay masks, lithographs and more, all of which appear in the museum’s exhibit. One of my favorite works was a display of her spiral-bound notebooks, the pages of which were interspersed with paintings by her children.

Ruth Asawa’s life and work remind me that all the things that feel like separate dimensions of my life (caregiving, teaching, creativity, community) are really just one thing: my life. Perhaps like her, I’ve learned that the more my making practices exist in the physical world, the more opportunities there are for my children to enter these practices with me. So: I revise by hand, physically cutting and pasting the lines of every new draft with an Exacto knife and glue stick; I write and send postcards via snail mail, darn socks and mend jeans the old-fashioned way—and my kids, observing these visible, embodied processes, mimic and/or join me with projects of their own.

❤️️ if you’re inspired by Mia’s wide-ranging creative practice, clicking the little red heart at the top or bottom of this page will help other good creatures find us! ❤️️

Is there something specific you do to jumpstart creativity?

You’re totally right in saying that there’s a switch that needs to be activated to make that jump between the creative- and care-giving brains. I experience this as a kind of downshift in my nervous system; my morning cup of tea, the candle I light after sending my kids off to school, the stacks of notebooks and reading material and half-finished drafts I let spread across the dining table—all these external cues help me to settle into what my kids call “morning brain,” that feeling, intuitive region of the self where my creativity hides. Often those solitary morning hours are my most satisfying time for creative work, perhaps because on some level, the creative mind wants to know that its surroundings are safe; somehow, it’s reassuring when the same things happen each day in the same way—a security that, by some strange paradox, allows the wilder, more unpredictable parts of my mind to emerge.

Sometimes it also helps to tune into a specific soundscape—Kali Malone’s organ compositions or Adrienne Lenker’s instrumentals, for instance, or maybe Gelsay Bell and Erin Rogers’s collaboration Skylighght. I believe pretty strongly that being a “good poet” is mostly about listening—to one’s surroundings, of course, but also to one’s interior life, so when I sit down to write, I try to begin by establishing a connection with my internal world. Megan Kaminski’s Prairie Divination deck is a tool I often turn to, along with this feelings wheel (which I like to cross-reference with Nature’s Palette: A Color Reference System from the Natural World).

What’s your creative philosophy and how has it expanded with the addition of caregiving?

Through my mothering (and honestly, gardening and therapy as well), I’ve become more attuned to processes of growth, and their relationship to attention and care. I have more trust, too, in the value of process itself, no matter what form it may take. I’m surrounded by growing things all the time, and the best / only thing I can do is to help shape what’s already emerging naturally, to be like the gardener that psychologist Alison Gopnik talks about in her book The Gardener and the Carpenter. There are certainly elements of “building” and “construction” in my writing, but as a whole, the process feels completely fluid to me; organic, intuitive, and nonlinear, circling back to the same material from different angles, veering off into new territory on a whim or associative thread. I suppose my philosophy is that every creative work has its own life, and that my job is just to pay attention to whatever appears to be ready, at any given moment, to emerge into the next incarnation of its existence. For a poem, this could mean cutting back in one moment, then adding more layers in the next. Reading, revising, note-taking, editing—these are all just expressions of its ongoing life, a process that, like all growth, occurs slowly and as a result of sustained care.

Mia Ayumi Malhotra is the author of Mothersalt (Alice James Books, May 2025) and Isako Isako, a California Book Award finalist and winner of the Alice James Award, Nautilus Gold Award for Poetry, National Indie Excellence Award, and Maine Literary Award. She is also the author of the chapbook Notes from the Birth Year. Mia is a Kundiman Fellow and founding member of The Ruby SF, a gathering space for women, transfeminine, and nonbinary artists. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she teaches poetry and writes about music and the interior life.

You can read more about Mia’s writing on her website; and if you’re in the Bay Area, New York, or Seattle this summer, check out her events page and join her at one of her upcoming Mothersalt book tour events.

Interested in reading the book? Ask your local library to order a copy, or purchase one from Alice James Books, Bookshop.org, or your neighborhood bookstore.

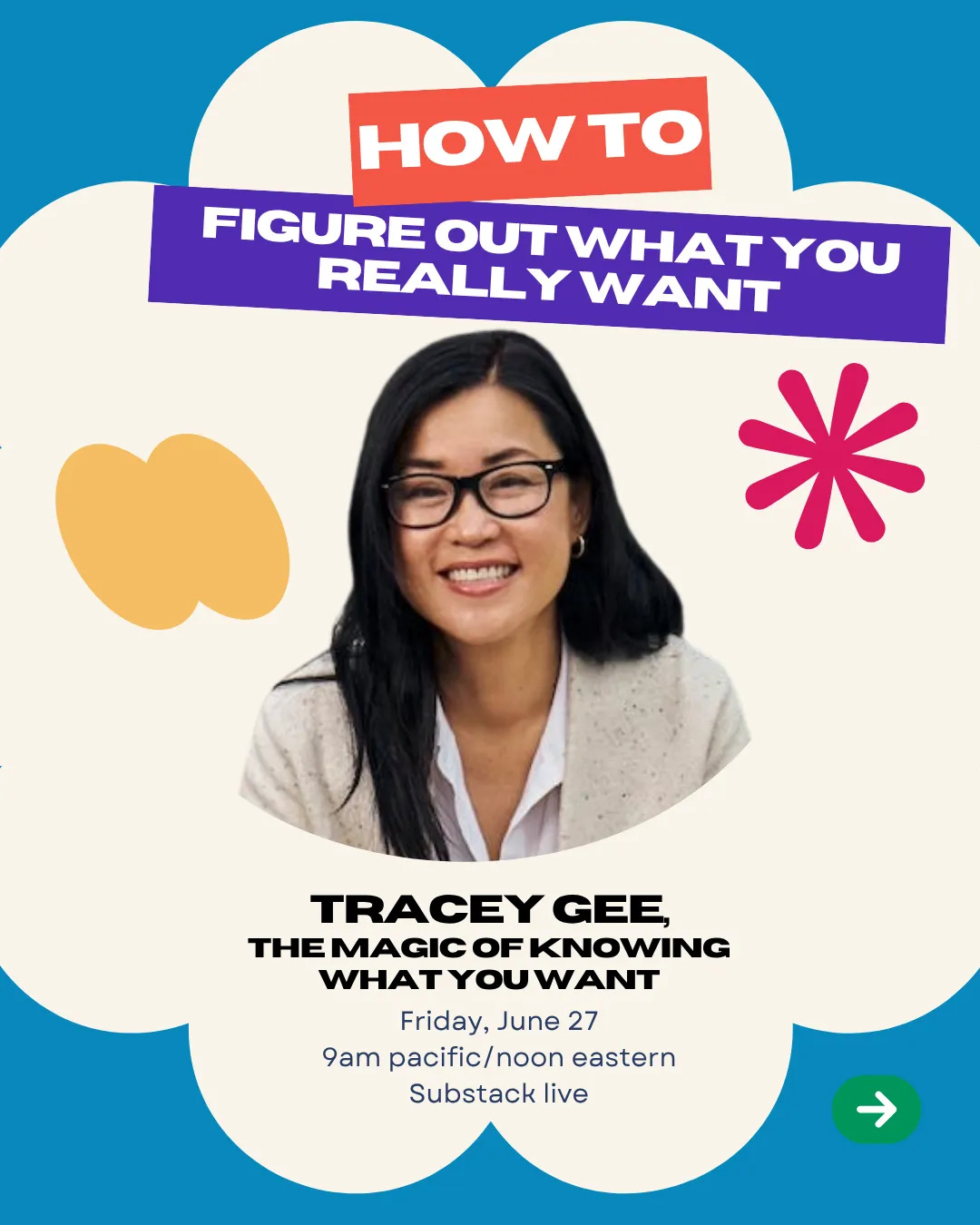

🌟this Friday, figure out what you really want with Tracey Gee🌟

Tomorrow, for our first Summer Friday chat, I’ll be in conversation with

, whose great book The Magic of Knowing What You Want is an essential guide for anyone who finds themself looking up from their to-do list and all the milestones they thought they were supposed to be working toward, only to wonder, but what do I really want?We’ll be chatting via Substack Live at 9am pacific/noon eastern, and you can join us! If you’re a subscriber, you’ll get an email when we go live, or you should be able to find us in Substack. If you can’t make it, I’ll share the recording afterward.

And you can read all about the whole Summer Fridays series here:

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. I’m so glad you’re here.

If Write More has helped you in your creative life, you can support me by sharing it online or with a friend, or by ordering my new book, The Good Mother Myth.

I enjoyed reading this and I will be buying Mothersalt! Can't wait to read it!

Love this interview. I first came across Mia in her interview for Be Where You Are and have since immersed myself in Mothersalt-such a beautiful book.