Discover more from Write More, Be Less Careful

this tornado loves you

linked poems and obsessions: an interview with poets Emily Perez and Sara Moore Wagner + a chance to Getaway and write with me this winter

Welcome to Write More! This is the your mid-month pop-in, which comes with encouragement and ideas to keep you going. I also send out a monthly intentions email on the last Sunday before a new month starts that aims to help you think through your goals and intentions for your writing practice in the coming month and to reflect on your progress in the previous month.

My friend Erinn always says that a book of poems should be like an album—if there’s 12 songs on the album, the 13th song is the album as a whole. I never fully got that idea until I listened to Neko Case’s Middle Cyclone—out of order.

I loved a bunch of songs individually, but the overall experience was disorienting. On the CD my husband burned for me (2009 was truly a different era), the songs somehow got jumbled. “Marais La Nuit,” a 30-minute recording of frog sounds, popped up in the middle. Placed at the end of the album, where it belongs, it’s beautiful and weird and somehow perfect. Out of order, it’s just . . . confusing. It wasn’t until I heard the full album, arranged as Case meant it, that I really got it: the individual songs were great, but arranged in the right order, it was an experience.

And that’s how I feel about a book of poems. It can be hard to find the right sequence, but once you do, it all just clicks. Writing poems in a series, whether they’re united by content or form or another obsession, can be one way to help find that magic right order that helps the whole thing click.

series poems as obsession and touchpoint: an interview with poets Emily Pérez and Sara Moore Wagner

Today we’ve got a great double interview with poets Emily Pérez and Sara Moore Wagner. I wanted to talk to them together because their new books both use series to ask big questions about gender and patriarchy and identity and domesticity.

Emily Pérez is the author of What Flies Want, winner of the Iowa Prize (University of Iowa Press, May 2022). Her other books and chapbooks include House of Sugar, House of Stone (Center for Literary Publishing, 2016), Made and Unmade (Madhouse Press, 2019) and Backyard Migration Route (Finishing Line Press, 2011). (Emily and I also edited The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood together.) She is a high school teacher and grade level dean in Denver where she lives with her family. You can find her on twitter and on instagram and find links to her poems and reviews on her website.

Sara Moore Wagner is the author of two full length books of poetry, Swan Wife [which I blurbed and loved!] (winner of the 2021 Cider Press Review Editors Prize) and Hillbilly Madonna (2020 Driftwood Press Manuscript prize winner), a recipient of a 2022 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council, a 2021 National Poetry Series Finalist, and the recipient of a 2019 Sustainable Arts Foundation award. She lives in West Chester, OH with her filmmaker husband Jon D. Wagner and their children, Daisy, Vivienne, and Cohen. You can find her on twitter and read poems and interviews on her website.

In our conversation, Emily and Sara shared insights about their own writing process and offered a bunch of great reading suggestions and tips for getting started writing your own series. (We’re talking specifically here about poetry, but I think you could adapt their advice for other forms, too, like flash nonfiction.)

Nancy

How did these series come about? Did you set out to intentionally write linked poems?

Emily

Both cases are a bit of chicken and egg. I did not intend to write linked poems, but I was writing clusters of poems around certain themes. As I started pulling the book together, I realized I had several poems with the same title: “My Son Is” and “How I Learned to Be a Girl.” (Eventually, only one “How I Learned to Be a Girl” poem made it into the book.) I did not think of these as linked poems or a narrative series, but rather, different attempts to investigate the same question.

Sara

I agree with Emily! Mine were also pretty chicken and egg in nature. As I was writing the series poems I have in this book, I did have a vague idea that maybe someday they would be linked. The “Complex” poems were less aware of that, and based, really, on the Freudian concepts of the Electra and Oedipus Complexes. I wanted to speak about the experience of being a woman in another way, a way that wasn’t quite “self portrait.” The “Housewife as” poems were another take on the self portrait poems, another, more collective way of saying that, and many of those did come after I had the idea for the book as a whole and were more intentionally linked.

Nancy

Emily, you have 4 poems with the title “My Son Is,” and I was really interested that they all have the same title, but formally they’re really different. (The first, for example, is pretty lyric–lots of sentence fragments, very image-driven, but it has some complete sentences and hints at a story–while the second is a really dense sonic knot of compound nouns.) How did that series evolve?

Emily

Before I answer, I want to note that in real life I have two children and one considers themself nonbinary and one considers himself male. Because the nonbinary child came out after most of these poems were written, and because my book is about learning gendered roles, I gender “the child” and “the children” in the book male.

As for the question: my child was developing depression, and I felt terrified and unequal to it. I kept asking myself the same questions–who is this child and how might I keep him alive? How might I parent effectively? The secondary questions were about nature and nurture–what had I passed on through my genes, and what environmental triggers had I created?

You note the different forms of the poems; I think that speaks to the fact that the poems were meditations from different times on the same set of questions.

When I was putting together the book and had several poems with the same title, I placed them not to show the development of my child (they are not ordered chronologically), but instead to show my own / the speaker’s evolving ideas about who her child is and her role in his mental health journey. The last poem in the group originally had a different title–“Diagnosis.” It is more about the parents than it is about the child, but I realized I wanted it to close out the “My Son Is” series because it spoke to some of the larger questions about the role of parents.

Nancy

What Flies Want also includes 3 poems whose titles suggest a kind of mini narrative arc across the book: “Before I Learned to Be a Girl,” “How I Learned to Be a Girl,” and “Once I Learned to Be a Girl.” I’m really interested in the tension between those titles and the narrative arc they imply and the poems themselves, which are much less narrative and explanatory than a reader might guess. How did those poems come together?

Emily

I had two poems called “How I Learned to Be a Girl” and one poem called “Before I Learned to Be a Girl” when I was pulling together the manuscript. Only one of the “How I” poems made it in. I did not write these poems in relation to one another, but they were all responses to being a woman in a patriarchy.

I knew the book would have three sections, and I had placed “Before I” in the first section and “How I” in the second section. That’s when I knew the book needed a “Once I” poem. I took a poem that was already in the third section, previously titled “Made and Unmade” and I changed the title to “Once I Learned to Be a Girl.” So again, the series was a bit of a chicken and egg process.

In this case, I did think of these poems as a progression. In “Before I Learned to Be a Girl,” the speaker is liberated and powerful, and associated with many activities typically gendered male–adventuring, fighting, pillaging. In “How I Learned to Be a Girl,” the speaker is reflecting on her childhood training in submission and pandering, and her resulting trapped position. The final poem, “Once I Learned to Be a Girl,” takes the happily ever after of fairy tales–how love and marriage are supposed to result in fulfillment–and turns this around to where the speaker realizes she’s lost herself.

These poems loosely trace the arc of the book, in that the first section looks at children learning gendered roles, the second section looks at being female in a patriarchy, and the last looks more critically at marriage.

Nancy

Sara, you have six poems grouped together under the title “Mentor Study” – Psyche Complex, Isis Complex, Penelope Complex, Beatrice Complex, Circe Complex, and Venus Complex. How did you come to put those figures together?

Sara

When I was arranging this book, I was researching the hero’s journey story arc, and reading Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces. I was thinking about how masculine that journey is, how someone like Odysseus or Dante are guided by steady hands, like Athena or the Sybil, to their greater purposes. I knew I wanted to structure my book, a quiet exploration of how not to lose the self in marriage, as a hero’s journey as a way to subvert what makes a story heroic.

When thinking about the concept of a mentor, which literally comes from the fake name Athena gave Odysseus as she stood by him, I was drawn to the great wives and mistresses of myth and literature, those who represent what a woman should or should not be, who were written to guide us in one way or the other into our traditional roles, whether it’s through their passionate mistakes (like Psyche or Circe or Venus, or through being held up as “pillars” of what a woman should be, like Isis or Beatrice or Penelope, the best wife of all).

I had a lot more “complex” poems than these, but I wanted to distill it down to those women who represent both sides of what I was meant to be or avoid. I was supposed to be a Penelope, not a Circe, but I had both in me (and so did they, likely, if they were based on anyone real). So those complex poems are more about breaking the tropes apart than continuing them, about saying we are all flawed and all worthy.

You can help other people find this newsletter by clicking the little heart at the top or bottom of this email!

Nancy

Sara, I love the Housewife as ___ series, which includes “Housewife as Rumpelstilskin,” “Housewife as Anastasia Romanov,” “Housewife as an August Morning,” and more. I particularly like the playfulness of it, and how the objects of each comparison are so different. How did you develop that series?

Sara

For the Housewife poems, I had a strong desire to make them the opposite of the Complex poems. While the Complex poems explore tropes related to women and wives, the housewife poems are persona poems in which the housewife inhabits a form that is opposite or contradictory to the nature of a “housewife.” Rumplestiltskin, for instance, is one of our most recognizable fairy tale tricksters. He’s self-serving in every instance, and he’s defeated by others learning his name, by tricking the trickster.

I have always been someone who can find myself in stories like this. As a housewife, too, sometimes what we say we want (time for ourselves, careers, to write books of poetry about not wanting to be a housewife) is seen as selfish. We conform to things and in doing so will bring about our own ending or erasure.

My purpose in these poems is to show that a “housewife” is not one thing or the other, but maybe all of these things. I can hold much more than the expectations placed on me the moment I became a wife and mother, and sometimes, I can explode those expectations in order to find something more sustaining. I was so interested in confronting the reader with juxtaposition in these poems, so they might question their own stereotypes and expectations.

Nancy

What other books that use series would you recommend readers take a look at?

Emily

I have always loved books with series poems as they feel like an ordering structure that helps me make sense of the book and the author’s priorities. I think of the series poems as touchpoints, both a place to rest and a place to galvanize the rest of the reading.

A few that have stuck with me:

James Allen Hall’s “Portrait of My Mother as” series, which morphs into a “Portrait of My Lover as” series in Now You’re the Enemy (University of Arkansas Press, 2008).

Ángel Garcia’s series “El Esposo de La Llorona” (the husband of La Llorona) in Teeth Never Sleep (University of Arkansas Press, 2018)

Yesenia Montilla’s forthcoming Muse Found in a Colonized Body (Four Way Books, 2022) has many “Muse Found in” poems that complicate the idea of the muse and where she can appear.

In Terrance Hayes’s American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin (Penguin, 2018), every poem has the same title which is both brilliant and frustrating and calls into question what makes a series.

Sara

Oh I just love a good series, always! In Pauletta Hansel’s recent book Heartbreak Tree, she has two series of poems (“Story” and “Letter to Myself at 15”) that run through the whole book. These poems provide a lot of context for the rest of the poems, showing us the speaker’s childhood, and the generational trauma and history she springs from, deepening the entire manuscript.

One of my favorite books is Mary Szybist’s Incarnadine, her “Annunciation as” poems are so weird and often political, and also show opposite concepts. She contrasts the annunciation, or the angel Gabriel announcing to Mary that she’s pregnant, with things like George Bush and Lolita, which makes us question our ideas about the Annunciation. It also feels personal, in that we hear the poet Mary in the name Mary. I love all of the layers there, and how much that brings to the rest of the book, which feels holy.

Also, Patricia Smith’s Incendiary Art wows, always, and has several series poems. Her series of “Choose Your Own Adventure” poems about Emmett Till are stunning in their gravity, creating a world where you can imagine another ending for him again and again. That resurfacing draws the reader back in such a powerful way. It’s a must read.

Nancy

For writers who are interested in working in a series, any advice or exercises you’d recommend?

Emily

Since I’ve stumbled into writing series poems rather than planned to write series poems, my main advice would be if you are interested in series, look at what you already have and consider what might be a series, then re-title accordingly.

In my current work in progress, I am being more deliberate about a series. These are “Have You Seen Yourself” poems, such as “Have You Seen Yourself from Behind?” and “Have You Seen Yourself On Screen?” I’m asking the same underlying question–how do we see ourselves?--through different contexts, to find what that reveals.

Sara

I absolutely agree with this advice! Sometimes you are writing a series and you have no idea it’s that until you’re in the manuscript phase and you can see connecting tissue. In my case, it was the two different ways my persona poems were functioning.

Series poems feel like obsession to me, in the best way. What are you obsessed with? I also think sometimes you know you aren’t finished with an idea. If you’re returning to the same image or concept, could there be a title or a part of a title to join them in a clearer way for the reader? I am still writing Complex poems and I may never stop because that is part of my identity. I’m drawn to story, to finding myself in narratives, so I will always have complexes. What is that for you? Is there an obsession or object or image you keep tripping over, like the Annunication or the word “Housewife,” something sticky you want to either define and redefine? Enter there.

Getaway and write with me this January!

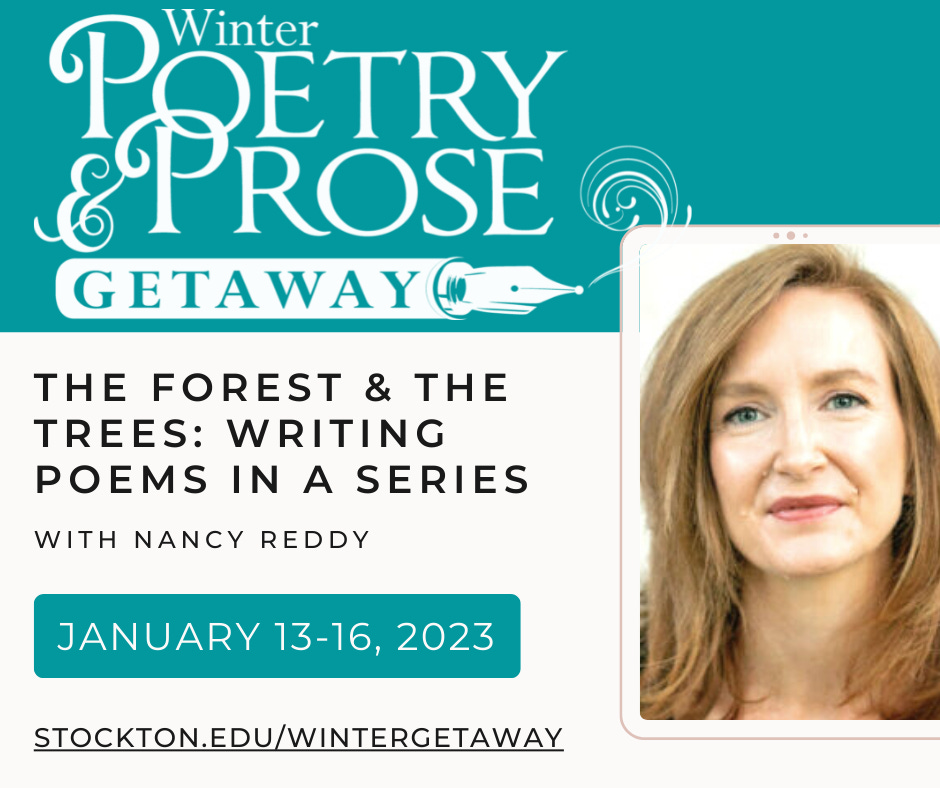

If you’re interested in trying your hand at writing poems in a series, I’m teaching a workshop, The Forest & The Trees: Writing Poems in a Series, at the Murphy Writing Winter Poetry & Prose Getaway this January on just that topic! I’ve loved the encouraging, generative spirit of the Getaway in the past as a participant, and I’m so thrilled to be joining this year as a workshop leader. Early registration discounts and scholarships are available; the Toni Brown Memorial Scholarship is for writers ages 31+ and the Robert Hayden Scholarship is for writers ages 18-30, with at least two Robert Hayden scholarships designated for young writers of color. The scholarship application deadline is November 15. You can read more about the Getaway and the workshops being offered here.

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. Have a victory or an epiphany in your writing life you’d like to share? A struggle you’d like help with? Reply to this email, comment below, or find me on twitter (@nancy_reddy) and instagram (@nancy.o.reddy).

If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, I’d love it if you would share it or send it to a friend.

Subscribe to Write More, Be Less Careful

why writing is hard & how to do it anyway