Discover more from Write More, Be Less Careful

how Wolfish author Erica Berry approaches research as "a deeply omnivorous act"

Cornell boxes, citation as conversation, and free association as a starting point for writing and research

Today I’m excited to share another interview in the new tending section, which will be a mix of essays and interviews about creative practice that do a deeper dive into a particular craft element or process question. I’m experimenting with an interview + exercise format, so below you’ll find just one interview question, then a fun exercise related to that question.

Today’s interview is with , a nonfiction writer whose amazing book Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell about Fear is one of my favorites from the year. You can find Erica on social media at @ericajberry, and she also writes the newsletter Away Message.

I’d love your suggestions of other writers and artists to feature in this series, so if you have a good idea, feel free to let me know.

I was wandering through the book fair at this past year’s AWP in Seattle when I turned and found myself face to face with Erica Berry, signing copies of her book, Wolfish, which I felt like I’d been reading about everywhere for weeks. Based on an essay of hers I’d read in The Guardian and an interview in Lit Hub, I had a feeling her book did something—intertwining personal narrative with deep research across multiple disciplines—that I was trying to figure out in my own writing, too. (She’s recently published a craft essay about associative research at The Millions that speaks to those questions, too.)

I loved Wolfish, and I know that it’s a book that I’ll keep returning to for its excellent writing and elegant structure. Below, Erica and I talk about her approach to research, and, in particular, the choices she made in how she brought that research into the narrative.

one question for Erica Berry

One of the things that really struck me as I was reading is your approach to citation–not just how you’re giving credit to the researchers whose work you draw on, but how you actually integrate their words and ideas.

had a really great piece on Lit Hub recently about writing with research, and she talked there about “how visible a writer makes their research.” Like Jaime, I’ve taught lots of first-year writing, and I think a lot in my own writing about when to quote and when to paraphrase or summarize. And I was taught in my PhD, which was in English, but in comp/rhet, which uses social sciences methods, an approach to writing with research that’s much more focused on the ideas than the specific words. So I’ve tended to think of paraphrase and summary as a way of building your authority as a writer.All of that to say–I really loved seeing you use so many direct quotations from such a wide range of writers, and sometimes without commenting on them much, or really spelling out the connection between the quotation and the rest of the text! (To give an example, across just two pages in the introduction, I see quotations and ideas from Native essayist Elissa Washuta, Alfred Hitchcock, journalist Isabel Wilkerson, poet and essayist Claudia Rankine, and social geographer Rachel Pain.) There are passages in your book that feel like this really rich textural collage. And I’d love to hear about how you came to that approach to integrating your research.

How did you come to this approach to citation? Were there some writers and researchers you wanted to make especially visible? I’m especially curious about how you thought about your approach to citation in terms of ethics and/or style.

Erica

This is such a good chewy question. Wolfish began to find its shape when I was getting my MFA, around the time I was introduced to Joseph Cornell’s assemblage “shadow boxes,” which are these surrealist 3D-scrapbooks of found materials. I loved the way his collages not only make room for the viewer to create their own narrative, but, by decontextualizing their contents, reorient our perceptions to it. A sea shell sitting beside an empty wine glass means something different than a shell on the beach.

I began to think about citation in a similar way, and to consider research--and weaving various threads of it together--as a deeply omnivorous act. My magpie brain is as drawn to quoting an Amazon review as it is to quoting a poet or a psychologist, because all of those sources are archival evidence of how a subject is seen and written about. Why cite and not just paraphrase? I have always been drawn to books that feel like good dinner parties, where lots of voices co-mingle--not just their ideas, but their speech--moving with a current of associative logic, maybe boomeranging off into a personal story before coming back. At some point I thought of my old math teacher berating us to “Show your work!” and I decided it felt important to quote the things that helped me reach conclusions. I wanted to share the shards of evidence I had found, in part because I wanted to guide the reader on their own journey of deduction.

I know that when I teach, a student is less likely to remember what I tell them than they are to remember what they say aloud in response. I wanted to make space for the reader to build their own connective tissue between 1) quotes on the page, 2) my authorial POV, and 3) their own lived experience. One of the best notes I got from a reader was that reading Wolfish made her nostalgic for college, that time when “material from all the disparate classes…was whirling in my head and connecting in super cool and interconnected ways.” My goal wasn’t just to teach about wolves, but to model a certain kind of generative, associative mode of being in the world. On an ethical level, this is a book that seeks to illuminate and dissolve the false binaries (human/animal, wolf/dog, nature/town, self/other, safe/danger) often employed to legitimize violence. I think one way to do that is by tuning ourselves to interconnection. My craft approach tries to compel that.

My goal wasn’t just to teach about wolves, but to model a certain kind of generative, associative mode of being in the world.

It’s also true that many of the people I first interviewed with a stake in wolf repopulation were cis white men between the ages of, say, 40-60. They were the biologists, ranchers, and conservationists. It felt essential to populate this book with a wider spectrum of perspectives and lived experience. Part of that meant talking to sources I rarely saw quoted in wolf-related media--like, say, Indigenous ranchers--but another part was including citations not just from people I interviewed, but people I read, because I felt “in conversation” with all of them. This is a book about both real and symbolic wolves, so Claudia Rankine writing about constructions of fear in post-911 America belongs just as much as biologist David Mech talking about how wolves eat. My brilliant editor Nadxi Nieto reminded me that quoting a text becomes a way of directing readers toward it. I’ve gotten multiple notes where a reader mentions how psyched they were to have followed a quote and discovered a new author or scholar they now love. I always dreamed this book might become a sort of ‘Trojan Horse,’ where maybe a guy comes to it because he’s a wolf fan, but while reading it he encounters the work of Sarah Ahmed, and then there’s no going back. Her voice is his head.

One last thing about Cornell’s boxes. They give the impression of someone who is extremely well traveled around Europe, but in fact he never went abroad. I thought about this detail when I struggled with my own authority: there were so many other wolf books in the library written by academics and biologists and people who had spent significant time beside the flesh-and-blood species, while I had never even seen a wolf in the wild! But my authority--like Cornell’s--was that I had spent a lot of time thinking about how ideas and information collided. As I write in the intro, I had “absorbed [the wolf], like osmosis” through my physical and cultural environments, and my goal with the book was to cite quotes to make that process of absorption clear. We do not just metabolize the natural world through lived experience, but through inherited stories. I wanted to show source material to help readers consider perhaps not only what they felt about wolves or fear, but why they felt that way.

if you’d like to try it out . . .

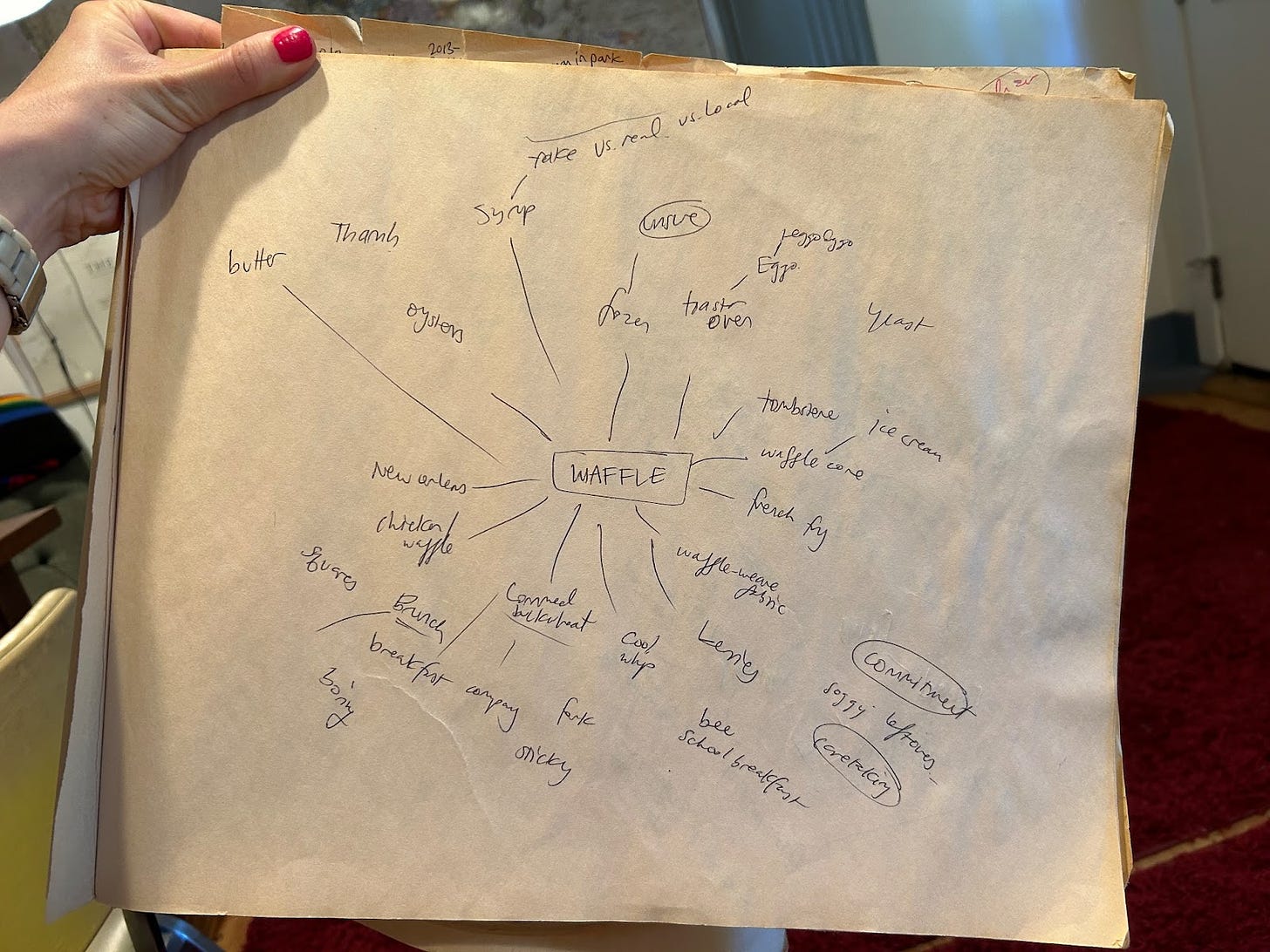

I start every project with a mind-map, to free up my associative/essayistic/lyrical way of thinking, and start to consider what corridors of research I might pursue. Basically I put my subject in the center of a sheet of paper (this is an oversized and quite tattered pad of newsprint I got at a garage sale) and then around it, write anything that comes to mind for, say, two minutes. I pause, and then further free-associate on the individual “spokes” from there.

Here’s a map that a class of mine collectively brainstormed. Everyone shouted out things that came to mind when they thought ‘waffle,’ and really interesting themes soon arose: the idea of being unsure, of commitment and caretaking, of fake vs. real. Would I then research the social history of Eggo waffles, or who their advertising targets, or maybe more philosophically about how we show one another care? It almost doesn’t matter. The act of mapping is generative in itself.

A prompt: Put an idea you are interested in writing about in the center of the page. Spend a few minutes mapping out all associations or questions that arise. They might have to do with memories, science or historical facts, physical observations, scraps of dialogue, references to folktales, art, quotes, songs/movies/books, metaphors, idioms. Now dig into a few of the individual “spokes,” creating mini mind-maps off of those categories. What interesting doors open up when you free yourself to think omnivorously, non-linearly?

If you want to hear more from Erica (how could you not?) you can sign up for her free monthly newsletter Away Message. You can get your very own signed copy of Wolfish from Broadway Books, Erica’s local bookstore.

Write More, Be Less Careful is a newsletter about why writing is hard & how to do it anyway. You can find my books here and read other recent writing here. If you’d like occasional dog photos, glimpses of my walks around town, and writing process snapshots, find me on instagram.

If Write More has helped you in your creative life, I’d love it if you would share it with a friend.

What a great interview! Now I must go devour this book like a wolf.

"The act of mapping is generative in itself." → LOVE this!! And somehow never thought of it this way. Makes me feel better for being such a crazy mindmapping nut 🤣